6. Appropriation and Synthesis in the Villa of Herodes Atticus at Eva (Loukou), Greece

- George Spyropoulos

Head of the Department of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities and the Department of Museums of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Corinth, Deputy Director of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Corinth

A syncretic blending of Egyptian, Greek, and Roman features can be found in varying degrees in Roman villas throughout the empire, including at the Villa Farnesina and the House of Augustus in Rome, Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli, and the villa of Herodes Atticus (AD 103–177), the noted Greek intellectual and cultural leader of Athenian ancestry, in Eva (Loukou), Greece (fig. 6.1). Recent scholarship recognizes that the cultural mixing of what could be considered typical Greek or Roman motifs with decorative Egyptianizing motifs “serve[d] as a stylistic reflection of an appropriation of . . . conquered cultures by means of integration” into a new imperial visual language.1 This paper will argue that what Jennifer Trimble described as “a sophisticated and imperializing Augustan engagement with pharaonic visual culture,” referring specifically to the Ara Pacis Augustae in light of the Egyptianizing of Rome’s urban landscape achieved by the two obelisks Augustus brought from Egypt to Rome, continued under Hadrian and is found in the splendid but subtle decorative elements in Herodes Atticus’s villa.2

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.1Robert Nelson characterized the appropriation of art and ideas across time and space as anything but neutral: “appropriation is not passive, objective, or disinterested, but active, subjective, and motivated.”3 Similarly, Trimble has observed, “Analyzing appropriation . . . means looking not only at the movement of artistic ideas, but asking why certain forms or motifs were taken up for a new purpose, what happened to them in that transformation, and what resonance and significance they had in their new settings.”4 In considering the visual semantic program of the villa of Herodes Atticus, these questions must be considered. What does the varied, eclectic composition of the villa’s architecture and decorative program mean?

The appropriation and recombination of multiple cultural influences appear frequently in Roman wall painting. Frescoes in Roman houses inspired by diverse civilizations developed a style of their own that reflected and supported not only social status but also the persona of the homeowner. Because of this, they can be viewed as “playfully allusive to contemporary cultural and political concerns. . . . It was at this moment in Western culture that art began to look back on itself with humor and intelligence rather than awe and that a native Roman secularism produced a culture tied to the forms of the past but also wedded to the great future of the Empire.”5As Megan Farlow has discussed, “The public interests of the Augustan age in globalization, a return to tradition, religion, and piety, and the revival of the mos maiorum (customs of the ancestors) intersect in the wall paintings of two houses in Rome associated with the imperial family: the House of Augustus on the Palatine (ca. 27 BCE) and the Villa Farnesina in the Campus Martius (ca. 21 BCE).”6 These themes are also prominent in Trimble’s study of the Ara Pacis, a monument that offers a “rich and carefully constructed synthesis of Egyptian, Hellenizing and Italic ideas and traditions, a layered and allusive monument to Rome’s incorporation of distant cultures, past times, and powerful traditions of political symbolism.”7 Trimble argues that the Egyptianizing allusions found in the Ara Pacis might best be understood through comparison with Egyptian precedents like the White Chapel of Senwosret I at Karnak (with which it shares architectural similarities); the Temple of Hathor at Dendera; and the Ptolemaic pronaos at Kom Ombo, where one might easily detect the Egyptian practice of decorating a structure’s exterior walls with registers of figural scenes above and a plant zone below.8 In contrast with the Augustan villas, where, among other motifs, Egyptianizing allusions comment on Augustus’s power, the villa of Herodes Atticus combines a synthesis of past styles with a variety of intentional allusions to create a synthetic program of decoration that had specific meaning for its patron.

Before excavation the villa of Herodes Atticus at Eva (Loukou) rose as a mound amid the hollows and ravines of the site. A kiln in operation from around 1950 had burned many ancient finds for lime, and innumerable marble chips covered the uncultivated area in heaps. The entire area was expropriated and secured, and plowing and the cultivation of olive trees were prohibited in order to protect the villa from further damage. In 1979 systematic excavation began under the supervision of Theodore Spyropoulos.

Many parts of the villa were covered by thick bushes, the roots of which had grown deep into the ancient remains and caused, in some cases, serious damage to the mosaic pavements. As was reported by the excavator, modern agricultural activity and the exploitation of the arable strips of land around the villa had moved several antiquities as far as hundreds of meters to the north and to the south. Some portrait heads, now in the Archaeological Museum of Astros, were found mutilated by plowing on the lower level to the north of the villa.

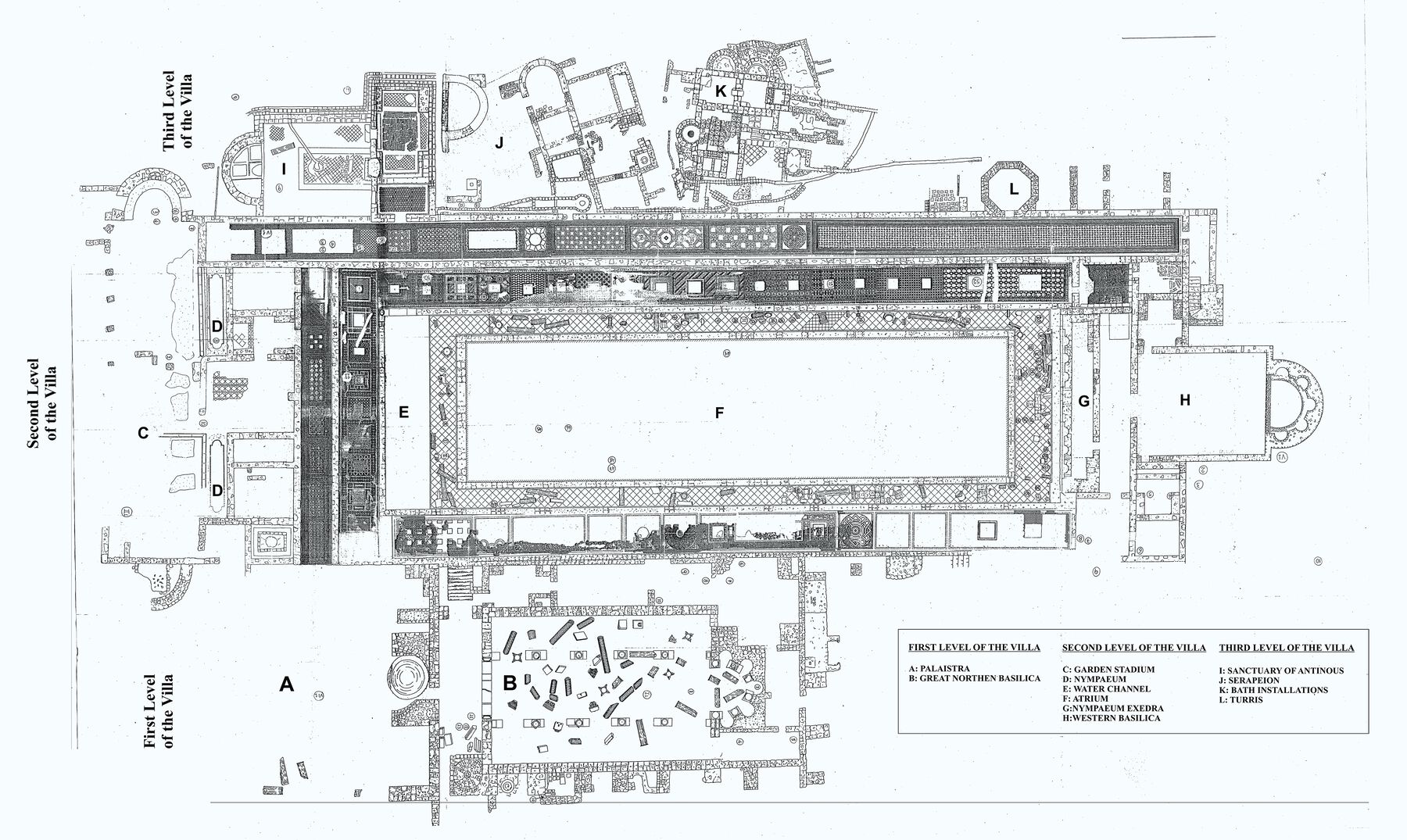

The villa is arranged on three levels.9 The first part to be excavated was the monumental staircase that leads to the entrance of the Great Hall toward the northern end of the villa. The steps of the staircase are now covered by tiles but were originally revetted with schist plaques, fragments of which have been found either in situ or around the base of the staircase. The staircase leads somewhat steeply to the north, having as its starting point the mosaic pavements that form the surface of the villa’s upper level.

First Level of the Villa

The first level was deeper than the others due to natural land formation and was adapted to accept the heavy construction of a large hypostyle hall (Great Northern Basilica), a typical hypostylos aethousa with two rows of internal colonnades supporting the roof. The walls of the hall were constructed from rectangular ashlar blocks interrupted at regular intervals by courses of strips of flat bricks. Externally these were covered by a thick layer of plaster to which marble panels were attached, some of which are still in situ. The entrance to the hall contains a large marble lintel, its sides decorated with semicolumns. Stratigraphically the various parts of the monument present a divergent picture. The thick layer of debris of the destruction level, which covers the ruins, consists of reddish soil filled with small stones, tiles, and fragments of schist and marble slabs, as well as bricks and plaster from the walls, including the mural decorations and the pavements of the villa. Inside the Great Hall this layer measures up to 3.5 meters high, a huge mass of rubble, which was kept in place thanks to the preservation of the strong walls of the building. This layer has not been removed since it fell and covered the hall, which occurred after it was found plundered and ransacked. The columns and the capitals were found at different levels of the layer of destruction, testifying to a gradual collapse of the deserted villa. Vandalism should not be excluded as the first and main destructive agent, and this might reasonably be attributed to the invasion of the Visigoths in the Peloponnese at the end of the fourth century AD.

The axiality of the basilica was enhanced by the addition of an apse on the west side with five niches for statuary and columns of Cipollino marble projecting between them. The surface of the mass of the walls was enlivened by reflected light and shadow in much the same style as the illusions of recesses and projections in the wall paintings of the villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, “an exceptional example of late Second Style decoration, teasing the eye with perspectival recession” and encouraging viewers to look above the barrier of the socle “and out into fantastic panoramas or architectural confections.”10 The columns of the main core of the basilica are also unfluted monoliths of gray-green Cipollino marble. The capitals, which are composite, are of Pentelic marble and date from the Flavian period, while those of the apse are Hadrianic. Building work on the basilica seems therefore to have been carried out in two phases. The first phase provided Herodes with the main core of the basilica, built by his father, Tiberius Claudius Atticus, or even his grandfather Hipparchus, who might have purchased the land when the family fled to Sparta after Hipparchus had been accused of tyranny. In the second phase, during the lifetime of Herodes, the initial plan of the basilica was expanded by the addition of the apse on the west side, a palaestra on the east, and a turris (observation tower) on the northeast, while at the same time construction of the villa was nearing completion. The eastern part of the great hypostyle hall was transformed into a basilica during the early Christian era judging by the closing of the two narrower arched entrances at the east wall and the thick layer of lime on the inside of the same wall, on which two illegible inscriptions of this period were traced.

Among the sculptural decorations of the basilica is a colossal statue of Athena placed in one of the niches of the apse.11 Also discovered there were portraits of Herodes and his family,12 grave reliefs, and an inscribed stela of the Erechtheis tribe with the names of those who died at the Battle of Marathon, a monument to the heroized dead from the grave of the Athenians at Marathon. It is probably because of the importance of the battle to the Athenians that Herodes Atticus decided to integrate the stela into his villa, in accordance with the funerary tone and memorializing aspects of the site.13

Second, Upper Level of the Villa

The second, upper level includes a garden terrace (belvedere), well defined by two walls running from east to west and overlooking the Argolic Gulf. Moving to the west, next to the garden terrace is a structure with a hairpin-shaped plan, identified as the Garden-Stadion of the villa, comprising two nymphaea on the west side and two symmetrical rooms, while in the middle there was a court on a higher level, which served as a triclinium (large dining hall). The most important sculptures found in the Garden-Stadion are those belonging to the Dionysian thiasos—a statue of Dionysos, a statuette of Pan, and others—which clearly indicate that, as with Hadrian’s Villa, some parts of the villa evoked a bucolic landscape peopled with Dionysian figures that symbolized a carefree life.14 Two statues of Herakles were conceived as pendants, displayed as a symmetrical pair. A left hand of the hero holding the apples of the Hesperides was found, showing that the statue was probably a copy of the so-called Farnese Herakles, attributed to the fourth-century BC sculptor Lysippos. A headless statue holding the lion skin in his left hand and most probably a club in his now missing right hand is similar in both style and execution to the so-called Lansdowne Herakles, a Hadrianic copy of an original of the fourth century BC, clearly associated with the style of Skopas, currently on display at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles.15

On the same level, west of the Garden-Stadion and above the Great Northern Basilica, is the heart of the villa: the atrium and an open garden—skillfully adapted to the landscape—surrounded by a rectangular peristyle running from east to west.16 The second and main cluster of buildings was accommodated by an extensive artificial terrace. As William L. MacDonald has correctly remarked: “Of course making a terrace meant making level ground, but leveling alone would not produce one. A terrace must be elevated, its platform a level stretch, set well above an area or vista, whose existence was part of the terrace’s definition. Terrace building, a prime Roman occupation, invited the incorporated construction of cryptoportici, simultaneously lessening the amount of fill required and providing useful space.”17 Cryptoportici have not been found at Eva, although one probably lies under the floor of the south stoa. This upper part of the villa has suffered severely from the effects of cultivation, and its upper part was completely erased and planted with olive trees. Some trial trenches opened there have indicated that the space was plowed and cleaned and everything was removed and dispersed or embedded in modern retaining walls around the area.

The admirable adaptation of the residential and other buildings of the villa into the landscape of the site of Eva is apparent, a practice that has a long tradition in the Hellenistic world starting with Pergamon. It continued with the Delian house plans, framed in the Hellenistic urban architecture known also from Pella, Vergina, and elsewhere and followed by the aristocratic inhabitants of Pompeii and the cities of the Greco-Roman world. Planning was impacted by the topographic requirements of the site, but certain features are typical. There is usually a peristyle court with colonnades on all four sides, one of them sometimes equipped with an upper gallery (the so-called Rhodian portico). There is always a cistern beneath the court as well as mosaic pavements in the court, the passages, and the entrance lobbies and formal reception rooms that opened onto the colonnade. From the middle of the first century AD, Roman villas of wealthy citizens presented an internal court framed by colonnades on three sides only, judging by villas in Campania, Apulia, and Rome itself.18 Two basic architectural types emerged, both with origins in the East. The peristyle villas, direct descendants of Hellenistic palaces, are frequently reflected in Campanian wall paintings, though the porticus villas, according to Karl Swoboda, evolved from a long, narrow row of rooms opening onto a road or court.19

The planning of the villa of Herodes Atticus at Eva was in accordance with the architectural tradition of the Hellenistic metropolis and its survival or circumstantial alterations, which were introduced to suit the taste and the needs of the Roman aristocracy. From this point of view, Herodes Atticus is shown to be a citizen of two worlds and an heir of two cultural traditions, a fact that is underlined by the mosaic pavements as well as the sculptural groups discussed below. The villa of Herodes Atticus at Eva is, properly speaking, a villa maritima, lying about five kilometers from the coastal site of Thyrea. As Alexander McKay remarks, “Coastal estates were eagerly sought after with the advent of Hellenistic luxury to Italy after the wars of conquest abroad.” Such villas gradually became “the paradigm of luxury and an habitual topic for moralists and poets.”20

To imagine what the villa was like at the time of Herodes Atticus requires the reconstruction of the surviving elements. One may reasonably suppose that it was surrounded by a brick-built wall faced in marble and fronted by a fine peristyle. The floor consisted of a mosaic pavement, like the peridromos outside it. All around the peristyle a deep channel measuring 170 meters in length was constructed. First, a wide trench was cut in the native soil. The trench was smoothed externally and then covered by a retaining wall made of baked bricks, which were in turn plastered and painted red and blue. The pavement of the trench was also revetted with large orthogonal bricks, also plastered and painted. This artificial pool—an ingenious impluvium—was filled with water to create an allusion to a Nilotic setting (figs. 6.2, 6.3), like the channels in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli.21 An aqueduct brought water from a local spring in the mountains. Remains of this construction are still visible, comprising walls and columns and an intact bridge of the Roman imperial period.22 It is exactly there in the hollow ditch that most of the villa’s remarkable sculptures were found. The ditch was filled with rubble and soil, bricks, tiles, bases, columns, and capitals, as well as sculptures either from the atrium or from the peridromos and the stoas that run all around it. The filling of the ditch elucidates some details of the fortunes of the villa. In its upper layers, it contains brown soil, pebbles, and small stones from the arable estates, fragments of bricks and tiles from the atrium and the stoa, and chips and fragments of marble and schist slabs and even of sculpture. The debris below contained columns, capitals, fragments of statues, marble reliefs, and some pottery fragments of lamps of the Roman imperial and early Christian periods.

Figure 6.2

Figure 6.2Three sides of the atrium were expanded to stoas decorated with mosaic pavements. The mosaics of the villa testify to excellent skill in their execution and to a high artistic standard in their conception and composition. One can see here the devices of foreshortening and chiaroscuro and the three-dimensional quality of the famous compositions at Delos, Pompeii, and Sparta.23 The mosaics at Eva are highly decorative, enlivened in many cases by small rectangular panels representing women, most of them muses or nymphs, shown as either busts or figures in conventional gestures and poses, such as the nymph Arethusa, from the southern part of the peridromos. Their voluminous upper bodies resemble statues of the second century AD (like the Tragoedia from Pergamon), and their faces are rendered in a classicizing, eclectic style.24 The rich and densely woven geometric patterns are skillfully executed and endlessly repeated in a continuous, tapestry-like surface, which undeniably imitated the carpets that covered the corridors of the houses from Hellenistic Delos to Greco-Roman Pompeii and Sparta. Yet this continuity is only the result of the skillful juxtaposition of larger squares decorated with exactly the same repertory. They are impressive and enhance the effect of luxury and delicacy of the decorative components of the rich villa.

This impressive and thick peristyle enhanced the symmetry of the atrium and the ditch and opened the scenery to the stoas behind it. The columns of the stoas were, as in the Great Northern Basilica, of unfluted Cipollino marble with Corinthian capitals of white Pentelic marble like those of the main core of the basilica, which were fluted and elegantly carved with abundant use of a drill. The rear wall of the stoas has been only partly preserved. It was made of small stones, and its inner face was thickly plastered and then revetted with marble slabs, some of which were preserved in situ. The roof inclined inward and reached the edge of the ditch where the rain fell in. Many large fragments of roof tiles were uncovered in the relevant places. As to the shape of the stoas, some relics suggest a low wall base in the middle to bridge their relatively large depth. The rear walls were undeniably the place where the fine reliefs found in the excavation were attached. The west side of the atrium was occupied by a nymphaeum and an exedra erected upon it, an architectural construction ingeniously adapted to the setting of the villa’s main compartments, which can be restored as having a facade of rows of niches decorated with portraits of Herodes Atticus, his friends and companions, and the imperial family. Portraits include those of Hadrian (fig. 6.4), Septimius Severus, Marcus Aurelius, Commodus, Publius Vedius Antoninus, an unknown man dressed in a Greek mantle, an unknown woman (probably Elpiniki, daughter of Herodes Atticus), and Herodes Atticus himself.25 In the villa of Herodes Atticus, the portraits displayed in the exedra and the atrium were meant to act as companions for the visitors, recalling the memory of the dead. Some are posthumous commemorations of his wife, children, and adopted students, who all died very young, but it was a commemoration that had the primary purpose of placing an emphasis on Herodes Atticus himself.

Figure 6.4

Figure 6.4Below the portraits, the front side of the nymphaeum is pierced with six niches in which six statues of young girls in windblown drapery were originally placed. The young girls, of which one is almost fully preserved, have been identified as the Dancing Caryatids by the sculptor Kallimachos, a work of the last decade of the fifth century BC. Opposite and in exact correspondence with the Dancing Caryatids stood, instead of columns, six caryatids supporting the roof of the east stoa of the atrium, overlooking the river, and seven columns behind the caryatids, thus creating a small pavilion. It is hard not to see here the influence of Herodes Atticus himself and his close involvement in the architectural genesis of the site, which, as Trimble writes of the Ara Pacis, “is understood to embody multi-layered appropriations of the past, recombined in sophisticated and innovative ways to meet the needs of the present.”26 Everything indicates his propensity for assigning complex meanings to architectural forms and associating himself with the cosmos. Cosmic imagery was particularly popular in Roman architecture, as seen at the Pantheon in Rome and in Hadrian’s sprawling residence at Tivoli. Nowhere was there a better opportunity for cosmic expression than in imperial, and especially residential, architecture.27 One of the buildings at Hadrian’s villa—known as the Teatro Marittimo, or Island Enclosure—is very similar to one at the villa of Herodes Atticus. It consists of a colonnaded portico, within which is a circular canal with an island at its center.28 As far as the rest of the sculptural decoration of the main core of the villa is concerned, it should be noted that another statue of Dionysos indicates that this part of the villa, like the Garden-Stadion, also resembled a bucolic landscape inhabited by Dionysian figures. Portrait galleries abounded, statues of athletes evoked a Greek gymnasium, and decorative landscape and votive reliefs were attached to the rear walls of the three stoas.

At the north and south stoas of the villa, respectively, stood the famous Hellenistic sculptural groups: the Pasquino (Menelaus holding the body of Patroclus) and the group of Achilles with Penthesilea, with whom he fell in love after having mortally wounded her. Both are Roman copies of lost originals of the Hellenistic age. The Achilles and Penthesilea group has been found and reconstructed, but the Pasquino is lost. The discovery, however, of two mosaic pavements from the south and north stoas representing the groups prove that the Pasquino once stood there.

To the west, the border of the villa is designated by a large hall with an apse on the west side and five niches for statuary. This building has been identified as the Western Basilica. The two suites of rooms to the north and south of the basilica are likely sacella or lararia, since dedicatory inscriptions, as well as portraits, of a type often placed in lararia were discovered there.29 One of the side rooms of the basilica must have served as a sanctuary of Isis, judging by the discovery of the head and bust of Artemis Ephesia (fig. 6.5)30 and the portrait of a youth whose hairstyle is associated with followers of Isis.31

Figure 6.5

Figure 6.5South Side of the Villa, Third Level

The third level of the villa contains some very interesting installations. Starting from east to west and along the main axis, one encounters the Temple-Sanctuary of Antinous-Dionysos (fig. 6.6). The initial plan had the shape of a basilica with an apse on the east side. In the middle of the apse there was an impluvium revetted with large marble plaques, fragments of which have been preserved. The floor was lavishly decorated with polychrome marbles in a technique known as opus sectile. An orthogonal pedestal was found on the northwest corner of the building. A statue of Antinous-Dionysos (fig. 6.7) originally stood on a podium in the apse of the building.32 A head of Polydeukion (a pupil of Herodes who died young) and a headless female statue, probably Herodes’s wife, Regilla, were also found in the sanctuary. Next to the Temple-Sanctuary of Antinous was an apsidal building, the Serapeion, similar to the one at Hadrian’s Villa. The identification of the building as a Serapeion has been confirmed by the discovery of both complete and fragmentary statues of river gods (figs. 6.8, 6.9), similar to those depicted on the mosaic pavements at the adjacent southern stoa. A statue of Osiris (fig. 6.10) was also found in the Serapeion, while a marble sphinx, now in the storage rooms of the National Museum in Athens, might also come from this place. Once again, the use of Dionysiac themes, operating alongside Egyptianizing motifs, serves as a stylistic embodiment of an appropriation of conquered cultures.

Figure 6.7

Figure 6.7 Figure 6.9

Figure 6.9Next to the Serapeion is a bath complex,33 while an octagonal structure attached to the external wall of the southern corridor has been identified as a turris.34 It is preserved to a maximum height of 1.4 meters, but it was certainly built much higher, to either one or two stories. In its interior, innumerable fragments of polychrome marble pieces were collected; their various shapes indicate their use as components of a pavement in opus sectile, while larger fragments may have belonged to a revetment decoration. The elegant kiosk lies opposite the high pedestal on which the sculptural group of Achilles and Penthesilea stood, while two openings in the walls of the southern stoa and the long corridor ensured easy access to it. It must be underlined that these portals were at some point closed and plastered, probably during the last stages of the villa’s use, a fact implying general rearrangement of its original plan, perhaps during the barbarian invasions of the later third century AD. It is tempting to connect the exquisitely adorned octagonal building with a potential cult to the heroized group during Herodes’s lifetime and to speculate a later transformation of it into a tower during the troubled years of the late third century AD. Excavation in the Great Northern Basilica confirms a gradual change of the villa into a castrum-like palace, like Diocletian’s residence at Split, where such octagonal towers also exist, or like the Piazza Armerina imperial villa in Sicily of the late third to early fourth century. After Herodes Atticus’s death in AD 179, the villa at Eva was most probably bequeathed to the Roman imperial family, following a precedent that had been set centuries before by Attalus III, who also left the kingdom of Pergamon to Rome after his death in 133 BC. Emperors of Rome, from Hadrian to Septimius Severus, whose portraits have been found at Eva, made it their temporary residence. Septimius Severus at least may be credited with some extensions, ameliorations, and transformations of the villa to suit the fashion and spirit prevailing during the Severan dynasty.

Figure 6.7

Figure 6.7 Figure 6.9

Figure 6.9The Villa after AD 165–70: Religious Monumentality and Immortalization

In the years between AD 165 and 170, Herodes repeatedly suffered the loss of members of his family, including his wife and beloved foster sons. Overwhelmed with grief on each of their deaths and deeply and self-consciously aware of the power of memory as well as of its fragility, he commissioned statues and portraits to memorialize them, declaring them heroes. He even acted like a Homeric hero himself: he organized and founded games and had his villa transformed into a monumental mausoleum.35 Herodes Atticus, according to the ancient sources, always displayed his disapproval of the Stoics for their lack of feeling. He challenged them with the argument that humans need strong emotions.36 He showed a kind of recklessness before the authority of Marcus Aurelius that is reminiscent of the fearlessness of a philosopher before a tyrant.37 This type of careless audacity and excessive emotion is characteristic of yet another rhetorical figure, the hero, and is exemplified by mythical individuals such as Achilles and Menelaus.38 Indeed Herodes Atticus’s grief and his habit of stepping outside the social norms because of it are two of his most characteristic traits.39 This extreme emotionalism had an impact on the sculptural decoration of various parts of the villa but mainly on the sculptural program of the exedra and the Temple-Sanctuary of Antinous-Dionysos. As far as the exedra is concerned, the six niches in which the Dancing Caryatids of Kallimachos, a masterpiece of Greek art, once stood were replaced by arcosolia in which marble klinai with reclining figures, representing members of Herodes’s family, were placed. As to the temple-sanctuary, the initial plan of the building was expanded to the west by the addition of a structure with three rectangular niches, in which marble klinai were placed, again with reclining figures representing members of Herodes’s family.40 A large amount of pottery used to perform rituals came to light during the excavation of the area. Votive and banquet reliefs—as well as a beautiful relief with funerary connotations, which was part of a monument placed within the sanctuary—replaced the original sculptural decoration of the Antinoeum. The new decoration was a conscious departure from the fresco style that initially decorated the Antinoeum, which as an official style shuns emotion and seems to seek an iconographic vocabulary that would allow Herodes to depict the despair associated with the most immediate and intimate reaction to a loved one’s death. Antinous was worshipped as Dionysos, as also verified by the inscriptions (ΘΕΩΔΙΟΝΥΣΩ), and like his closest equivalent in the Egyptian pantheon, the god Osiris, he also suffered, died, and was resurrected, thus serving as a symbol of death and rebirth. The meaning of the display is clear: the reclining figures on the klinai of the temple-sanctuary would undergo the same transformation as the god Dionysos (Osiris) and would also be reborn.41

The original significance of the villa, its otium, which for the Romans meant indulging in philosophical speculation and time well spent and which was instinctively felt by anyone who entered the grounds, dissolved as the entire site was transformed into a mausoleum. The funerary, banqueting, and heroic reliefs; the proliferation of heroic art; the klinai with full-length portraits of the deceased; the introduction of feasts for the dead according to the requirements of the hero cult; and the incorporation of a memorial to the fallen of Marathon signaled the meaning of this vast mausoleum. Herodes Atticus forced the stela into the role of honoring the dead with all the glorious traditions of the Marathonomachoi (veterans of the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC). This, added to the transformation of the Temple-Sanctuary of Antinous-Dionysos into a mausoleum and the introduction of feasts for the dead according to the requirements of the hero cult and the proliferation of heroic art, suggests that Herodes Atticus was constructing a kind of commemorative monument of heroic virtue for himself and his deceased family.42 Even a reinstallation of the Menelaus and Achilles groups was incorporated into the plan. In the new display, the group, which had originally faced east (as clearly indicated by the accompanying mosaics), faced west—judging from the shape of the plinth, the pedestal, and the cuttings—toward the exedra that had been transformed into a mausoleum, thus becoming a place to mourn.

The exedra—a long wall pierced with niches for portrait display—did not look like the Western Wall in Jerusalem, which Herod the Great erected in his expansion of the Second Temple, but it certainly functioned like it. It was endowed with everlasting sanctity: “And I will make your sanctuaries desolate,” meaning that the sanctuaries retain their sanctity even when they are desolate, and they became the symbol of both devastation and hope.43 Herodes expressed his pain for the loss of his family members by reinstalling the dramatic Hellenistic sculptural groups and transforming the exedra into a sort of memorial monument and the temple-sanctuary into a mausoleum. The symbolic comparison of the exedra of the villa to the Western Wall in Jerusalem does have an evidentiary basis, and Jewish mourning practices and behaviors in the Roman period are attested.44 The presence of Tiberius Claudius Atticus, Herodes’s father, in Judaea is attested by the Christian chronicler Hegesippus, who records that he served as a legatus of Judaea from AD 99/100 to 102/103, as well as suffect consul.45 Heinrich Graetz argued that Atticus was the Roman governor mentioned in rabbinic traditions by the name of Agnitus.46 Richard Bauckham and E. Mary Smallwood make clear reference to Herodes’s father’s governorship in Judaea in the years AD 99/100–103,47 a date that coincides with the birth of Herodes. The family would have been familiar with Jewish ritual practices.

Trimble describes the Ara Pacis as a “richly layered, culturally allusive and semantically complex visual monument,” containing references that “could only have been directed toward the most knowledgeable people in Rome.”48 And the same can be said of the Villa Farnesina, the imperial villa at Boscotrecase, the House of Augustus, and Hadrian’s villa. Herodes Atticus, in contrast, built magnificently on private land to create a rich synthesis of Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and Jewish ideas and traditions.49 The transformation of the villa into a monument commemorating the deceased members of Herodes’s family must be interpreted as a reflection of his extreme grief, which compelled him to create a site of remembrance, one that is of a particular time but that also incorporates varied cultural and historical references.

Notes

, 34. See also ; . ↩︎

, 6. ↩︎

, 118. See also , 5–6 ↩︎

, 5. ↩︎

, 54. ↩︎

, 2. ↩︎

, 79–82; ; , 43. ↩︎

, 26. Trimble (, 40–41), also writes: “In the wall paintings from the Black Room of the Augustan villa of Boscotrecase, Egyptianizing images are found in particular places within the painted architectural framework. They do not appear, as is the case with the Ara Pacis, in the central spaces, which are reserved for sacro-idyllic landscapes and mythological scenes in a comparatively Hellenizing style, but are pictorial framing devices and evocative ancillary elements.” The yellow panels surmounting a central candelabrum recall Egyptian motifs, and the swans, which seem to appear in an arrangement similar to that in the Ara Pacis, could represent Augustus and his family: , 40–42. See also ; ; , with relevant bibliography. ↩︎

On the villa of Herodes Atticus, see ; , 34–38; ; ; ; ; ; M. E. Gorrini in , 64–70, nos. 43–47; ; , 392–95, with additional bibliography; , 432–36; , 98–108. ↩︎

See , 7. ↩︎

, 48–49. ↩︎

, 34–58. ↩︎

, 23–33; ; ; , 82–97. ↩︎

. ↩︎

Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, 70.AA.109, http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/6549/unknown-maker-statue-of-hercules-lansdowne-herakles-roman-about-ad-125/. On Skopas, see also . ↩︎

Corridors and porticoes are found among the villas of Campania destroyed by the eruption of AD 79. Both types are also represented in wall paintings of the same period. Some villas have two wings at right angles, or even three, like the villa at Eva (Loukou), when they begin to resemble the old peristyle type again; see , 312. ↩︎

, 114, 135. ↩︎

See ; , 135, 172. ↩︎

. ↩︎

, 115. ↩︎

Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli comprised “palaces, large and small, a guest hostel, basilica, pavilion, dining-rooms, baths, a library, porticoes, . . . pools, servants’ quarters, a stadium, cryptoportici, a palaestra, a vaulted temple of Serapis, and a complex of elongated pool and triclinia intended to recall Alexandria’s Canopus with overtones of Antinous, his lost beloved” (, 132). The villa of Nero at Sublaqueum (Subiaco) seems to be a bold forerunner of this scheme. It was designed as an inland villa maritima, and the river was dammed to create an artificial lake; see , 41–42. ↩︎

Rogers (, 173–92) rightly argues that there were similarities in the use of fountains among the two villa structures, especially in large, open-air spaces, courtyards, gardens, and dining spaces. ↩︎

See ; . ↩︎

See the statues from Lykosura; ; , 109–36; , 357–404, plates XII–XIV, figs. 1–25. ↩︎

A nymphaeum that featured two layers of eleven niches arranged in a semicircle was also built by Herodes Atticus at Olympia. The lower niches featured sculptures of the imperial family, and the upper contained sculptures of Herodes’s family in a slightly smaller scale. See ; , 131–32. On the portraits, see ; , 432–36. ↩︎

, 11. ↩︎

See , in which the villa of Herodes Atticus is used as a point of departure to examine the presence and influence of the cosmos in the architectural design and decorative details of Greco-Roman residential architecture. ↩︎

For a plan of the island enclosure at Hadrian’s Villa, see , 82, fig. 95; , 91, fig. 71. Of the enclosure, MacDonald and Pinto (, 89), state: “It is hard to resist the notion that some overriding meaning is expressed here symbolically. . . . We leave questions of possible cosmological references to others, but observe that this ingenious geometrical web and its circular government, with powers of implied radial expansion, could have had ideal connotations, could carry within it those strong implications of celestial shapes and paths found in other Roman art and architecture.” According to Davies (, 90), “Some scholars disagree over the building’s function and prototype. Some characterize it as the emperor’s retreat from the world, with a prototype in Plato’s description of Atlantis . . . or Herod the Great’s circular palace at Herodium.” ↩︎

Here was found the portrait of Lucius Ceionius Commodus, whom Hadrian publicly adopted as his chosen successor and was introduced into the Domus Augusta with the official title Aelius Caesar; see ; see also , 28. ↩︎

, 129–30, fig. 33; , 436. ↩︎

, 129. The best parallel is a portrait of Severus Alexander in Seville; see , 203; , 26, fig. 3. ↩︎

, 89–130. In Hadrian’s Villa, archaeologists found the remains of a substantial structure consisting of two small facing temple buildings in front of a large semicircular exedra. Fragments of Egyptian-like sculptures, as well as remnants of the outer walls of the temples with hieroglyphic inscriptions, leave no doubt that this was a sanctuary for Antinous himself; see , 181, fig. 160. ↩︎

It presents small rooms, paved and decorated with marble slabs. The luxury and wealth of the installation are to be seen in the abundant use of materials such as white marble slabs, onyx, lapis lacedaemonius, and rosso antico; the more valuable and costly materials were probably used only as fillets between the marble slabs, which covered the pavements and walls of the various parts of the bath complex; see . ↩︎

See ; . ↩︎

I discussed Herodes’s extravagant grief in detail in my lecture at the Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Atene, on December 8, 2017, “The Emergence of the Multifarious, Highly-Gifted, Intellectually Curious, Intertextual, Self-Ironizing and Destructive, yet Romanticised Personality of Herodes Atticus from the Subtle Echoes of His Estate at Eva/Loukou Kynourias.” See also , 183–222; , 20; , 190. ↩︎

, 248–49; on Herodes’s extravagant mourning, see also , 157–62. ↩︎

, 105. ↩︎

In the Iliad, for example, Achilles, having been overwhelmed with grief upon the death of Patroclus, lies down in the dirt, tears at his hair, and wails a terrible cry. An angry grief that surrounds the death of Hektor is also demonstrated by Priam himself. , 638–49; see also , 9–33, and , 197–201, with the relevant bibliography. Emotions being displayed through exaggeratedly expressive faces and gestures are best evidenced in the Hellenistic period, in such works as the sculptural groups of Menelaus and Achilles, both of which decorated the villa of Herodes Atticus. On the groups, see , 116–44; ; . ↩︎

, 105. ↩︎

; ; ; ; , 187. A detailed comparison with the nymphaeum of Herodes at Olympia, where changes to the statues and the addition of the monopteron (monopteroi) in the basin occurred, boost the argument for the transformation of the exedra into a commemorative family monument; see also ; ; on the Heroon of Antinous, see , 346–48. ↩︎

See ; ; , 1–7. For the appearance of the Antinoeum, see , 248–50. ↩︎

, 183–222; , 184–91. ↩︎

Leviticus 26:31. ↩︎

Jews mourning the Roman victory in Judaea (as well as other conquered peoples) are depicted on coins. See ; ; ; , 103–23; ; . ↩︎

Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica 3.32, 3, 6; , 131–33; , 194. ↩︎

, 22–23. ↩︎

, 131–33; , 92–94. ↩︎

, 46. ↩︎

, 43. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Anderson 1987–88

- Anderson, Maxwell L. 1987–88. “Pompeian Frescoes in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 45 (Winter): 3–54.

- Bauckham 2015

- Bauckham, Richard. 2015. Jude and the Relatives of Jesus in the Early Church. London: Bloomsbury.

- Blake 1959

- Blake, Marion Elizabeth. 1959. Roman Construction in Italy from Tiberius through the Flavians. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution.

- Bol 1984

- Bol, Renate. 1984. Das Statuenprogramm des Herodes-Atticus-Nympäums. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Brin 1986

- Brin, Howard B. 1986. Catalogue of Iudea Capta Coins. Minneapolis: Emmett.

- Bruneau 1972

- Bruneau, Philippe. 1972. Les mosaïques: Exploration archéologique de Délos. Paris: De Boccard.

- Butz 2015

- Butz, Patricia A. 2015. “The Stoichedon Arrangement of the New Marathon Stele from the Villa of Herodes Atticus at Kynouria.” In Ancient Documents and Their Contexts: First North American Congress of Greek and Latin Epigraphy (2011), edited by John Bodel and Nora Dimitrova, 82–97. Leiden: Brill.

- Calandra and Adembri 2014

- Calandra, Elena, and Benedetta Adembri, eds. 2014. Adriano e la Grecia: Villa Adriana tra classicità ed ellenismo. La Mostra. Milan: Electa.

- Castriota 1995

- Castriota, David. 1995. The Ara Pacis Augustae and the Imagery of Abundance in Later Greek and Early Roman Imperial Art. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Charbonneaux, Martin, and Villard 1973

- Charbonneaux, Jean, Roland Martin, and François Villard. 1973. Hellenistic Art, 330–50 BC. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Clarke 1991

- Clarke, John R. 1991. The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.–A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Cody 2003

- Cody, Jane M. 2003. “Conquerors and Conquered on Flavian Coins.” In Flavian Rome: Culture, Image, Text, edited by Anthony James Boyle and William J. Dominik, 103–23. Leiden: Brill.

- Davies 2000

- Davies, Penelope J. E. 2000. Death and the Emperor: Roman Imperial Funerary Monuments from Augustus to Marcus Aurelius. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dickins 1905–6

- Dickins, Guy. 1905–6. “Damophon of Messene.” Annual of the British School at Athens 12:109–36.

- Dickins 1906–7

- Dickins, Guy. 1906–7. “Damophon of Messene: II.” Annual of the British School at Athens 13:357–404.

- Eck, Holder, and Pangerl 2010

- Eck, Werner, Paul Holder, and Andreas Pangerl. 2010. “A Diploma for the Army of Britain in 132 and Hadrian’s Return to Rome from the East.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 174:189–200.

- Farlow 2016

- Farlow, Megan Michelle. 2016. “The House of Augustus and the Villa Farnesina: The New Values of the Imperial Interior Decorative Program.” Honor’s thesis, University of Iowa.

- Foss 1990

- Foss, Clive. 1990. Roman Historical Coins. London: Seaby.

- Galli 2017

- Galli, Marco. 2017. “Hadrian’s Forgotten Heir: A New Portrait of Aelius Caesar from Eva (Loukou).” Lecture presented at the Gennadius Library of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, November 9. https://www.ascsa.edu.gr/News/newsDetails/videocast-hadrians-forgotten-heir-a-new-portrait-of-aelius-caesar-from-eva.

- Gleason 2010

- Gleason, Maud W. 2010. “Making Space for Bicultural Identity: Herodes Atticus Commemorates Regilla.” In Local Knowledge and Microidentities in the Imperial Greek World, edited by Tim Whitmarsh, 125–62. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goette 1989

- Goette, Hans R. 1989. “Römische Kinderbildnisse mit Jugendlocken.” Athenische Mitteilungen 104:203–17.

- Graetz 1885

- Graetz, Heinrich. 1885. “Historische und topographische Streifzüge: Die Römischen Legaten in Judäa unter Domitian und Trajan und ihre Beziehung zu Juden und Christen.” Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums 34 (1): 17–34.

- Havelock 1971

- Havelock, Christine Mitchell. 1971. Hellenistic Art: The Art of the Classical World from the Death of Alexander the Great to the Battle of Actium. London: Phaidon.

- Kaehler 1958

- Kaehler, Heinz. 1958. Rom und seine Welt: Bilder zur Geschichte und Kultur. Munich: Bayerischer Schulbuch-Verlag.

- Kavvadias 1893

- Kavvadias, Panagiotes. 1893. Fouilles de Lycosoura: Livraison I; Sculptures de Damophon, Inscriptions. Athens: Vlastos.

- Kramer-Hajos 2015

- Kramer-Hajos, Margaretha. 2015. “Mourning on the Larnakes at Tanagra: Gender and Agency in Late Bronze Age Greece.” Hesperia 84 (October–December): 627–67.

- Lambert 1984

- Lambert, Royston. 1984. Beloved and God: The Story of Hadrian and Antinous. New York: Viking.

- Leon 2001

- Leon, Pilar. 2001. Retratos romanos de la Bética. Seville: Fundación El Monte.

- Levick 2005

- Levick, Barbara. 2005. Vespasian. London: Routledge.

- MacDonald 1986

- MacDonald, William L. 1986. The Architecture of the Roman Empire. Vol. 2, An Urban Appraisal. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- MacDonald and Pinto 1995

- MacDonald, William L., and John A. Pinto. 1995. Hadrian’s Villa and Its Legacy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- McKay 1977

- McKay, Alexander G. 1977. Houses, Villas and Palaces in the Roman World. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Meshorer 1982

- Meshorer, Jakob. 1982. Ancient Jewish Coinage. Vol. 2, Herod the Great through Bar Cochba. Dix Hills, NY: Amphora.

- Montalto 2013

- Montalto, Marco Tentori. 2013. “Nuove considerazioni sulla stele della tribù Erechtheis dalla villa di Erode Attico a Loukou-Eva kynourias.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 185:31–52.

- Nelson 1996

- Nelson, Robert S. 1996. “Appropriation.” In Critical Terms for Art History, edited by Robert S. Nelson and Richard Schiff, 116–28. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Neudecker 2014

- Neudecker, Richard. 2014. ”Die Villa Hadriana als Modell für Herodes Atticus.” In Adriano e la Grecia: Villa Adriana tra classicità ed ellenismo. Studi e ricerche, edited by Elena Calandra and Benedetta Adembri, 135–54. Milan: Electa.

- Opper 2008

- Opper, Thorsten. 2008. Hadrian: Empire and Conflict. London: British Museum Press.

- Papaioannou 2018

- Papaioannou, Maria. 2018. “Villas in Greece and the Islands.” The Roman Villa in the Mediterranean Basin: Late Republic to Late Antiquity, edited by Annalisa Marzano and Guy P. R. Métraux, 328–76. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pollitt 1986

- Pollitt, J. J. 1986. Art in the Hellenistic Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Robertson 1959

- Robertson, D. S. 1959. A Handbook of Greek and Roman Architecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rogers 2018

- Rogers, Dylan Kelby. 2018. “Shifting Tides: Approaches to the Public Water-Displays of Roman Greece.” In Great Waterworks in Roman Greece: Aqueducts and Monumental Fountain Structures, edited by Georgia A. Aristodemou and Theodosios P. Tassios, 173–92. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Rogers 2021

- Rogers, Dylan Kelby. 2021. “Sensing Water in Roman Greece: The Villa of Herodes Atticus at Eva-Loukou and the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Eleusis.” American Journal of Archaeology 125, no. 1 (January): 91–122.

- Rosso 2005

- Rosso, Emmanuelle. 2005. ”Idéologie impériale et art officiel sous les Flaviens: Formulation, diffusion et réception dans les provinces occidentales de l’empire romain (60–96 ap. J. C.).” PhD diss., Université Paris IV—Sorbonne.

- Smallwood 1962

- Smallwood, E. Mary. 1962. “Atticus, Legate of Judaea under Trajan.” Journal of Roman Studies 52:131–33.

- Smith 1991

- Smith, Roland R. R. 1991. Hellenistic Sculpture: A Handbook. London: Thames & Hudson.

- G. Spyropoulos 1995

- Spyropoulos, George. 1995. “The Villa of Herodes Atticus at Mone Loukou.” MA thesis, King’s College, London.

- G. Spyropoulos 2001

- Spyropoulos, George. 2001. Drei Meisterwerke der griechischen Plastik aus der Villa des Herodes Atticus zu Eva/Loukou. Frankfurt: Lang.

- G. Spyropoulos 2006a

- Spyropoulos, George. 2006a. Η έπαυλη του Ηρώδη Αττικού στην Ευα/Λουκού Κυνουρίας. Athens: Olkos.

- G. Spyropoulos 2006b

- Spyropoulos, George. 2006b. Νεκρόδειπνα, Ηρωικά ανάγλυφα και ο Ναός-Ηρώο του Αντίνοου στην έπαυλη του Ηρώδη Αττικού. Sparta: Poulokephalos.

- G. Spyropoulos 2009

- Spyropoulos, George. 2009. Οι Στήλες των πεσόντων στη μάχη του Μαραθώνα από την έπαυλη του Ηρώδη Αττικού στην Εύα Κυνουρίας. Athens: Kardamitsa Publications.

- G. Spyropoulos 2010

- Spyropoulos, George. 2010. “A New Statue of Herakles from the Villa of Herodes Attikos in Arkadia.” In Skopas of Paros: Abstracts Volume of the Third International Conference on the Archaeology of Paros and the Cyclades, edited by Dora Katsonopoulou, 65–66. Athens: Dora Katsonopoulou.

- G. Spyropoulos 2015a

- Spyropoulos, George. 2015a. “La villa de Herodes Attico en Eva/Loukou, Arcadia.” In Dioses, héroes y atletas: La imagen del cuerpo en la Grecia antigua, edited by Carmen Sánchez and Inmaculada Escobar, 392–95. Alcalá de Henares: Museo Arqueológico Regional.

- G. Spyropoulos 2015b

- Spyropoulos, George. 2015b. “Vivere e morire nell’impero.” In L’età dell’angoscia: Da Commodo a Diocleziano (180–305 d.C.), edited by Eugenio La Rocca, Claudio Parisi Presicce, and Annalisa Lo Monaco, 432–36. Rome: MondoMostre.

- G. Spyropoulos 2016

- Spyropoulos, George. 2016. “Herodes Atticus and the Greco-Roman World: Imperial Cosmos, Cosmic Allusions, Art and Culture in His Estate in Southern Peloponnese.” Lecture, Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University, September 13. https://isaw.nyu.edu/events/archive/2016/herodes-atticus-and-the-greco-roman-world-imperial-cosmos-cosmic-allusions-art-and-culture-in-his-estate-in-southern-peloponnese.

- G. Spyropoulos 2018

- Spyropoulos, George. 2018. “Ein besonderer Fall: Die Nekropole von Tanagra in Boeotien-Jenseitsvorstellungen.” In Mykene: Die sagenhafte Welt des Agamemnon, edited by Bernhard Steinmann, 197–201. Karlsruhe: Badisches Landesmuseum; Darmstadt: Zabern.

- T. Spyropoulos 1974

- Spyropoulos, Theodore G. 1974. “Ανασκαφή μυκηναϊκής Τανάγρας.” Prakt 129:9–33.

- T. Spyropoulos 1996–97

- Spyropoulos, Theodore G. 1996–97. “Villa of Herodes Atticus.” Archaeological Reports 43:34–38.

- T. Spyropoulos 2003

- Spyropoulos, Theodore G. 2003. “Prächtige Villa, Refugium und Musenstätte: Die Villa des Herodes Atticus im arkadischen Eua.” Antike Welt 34 (5): 463–70.

- Strazdins 2012

- Strazdins, Estelle A. 2012. “The Future of the Second Sophistic.” PhD diss., Balliol College, Oxford.

- Swoboda 1924

- Swoboda, Karl M. 1924. Römische und romanische Paläste: Eine architekturgeschichtliche Untersuchung. Vienna: Schroll.

- Thompson 1952

- Thompson, Homer A. 1952. “The Altar of Pity in the Athenian Agora.” Hesperia 21 (January–March): 79–82.

- Tobin 1997

- Tobin, Jennifer. 1997. Herodes Atticus and the City of Athens: Patronage and Conflict under the Antonines. Amsterdam: Gieben.

- Trimble 2007

- Trimble, Jennifer. 2007. “Pharaonic Egypt and the Ara Pacis in Augustan Rome.” Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics. http://www.princeton.edu/~pswpc/pdfs/trimble/090701.pdf.